Your weekly dose of Seriously Risky Business news is written by Tom Uren, edited by Patrick Gray with help from Catalin Cimpanu. It's supported by the Cyber Initiative at the Hewlett Foundation and founding corporate sponsor Proofpoint.

Ransomware is an ongoing scourge, but a recent report by a security researcher that infiltrated LockBit reveals opportunities for disruption.

Although we write about it less, ransomware hasn't gone away. Although data collection is far from ideal, a variety of sources tell similar stories — in terms of raw numbers, the number of ransomware incidents hitting organisations globally over the last few years hasn't changed much.

The groups involved have changed, however, and LockBit is currently the most prolific ransomware group, according to both The Record and threat intelligence firm KELA. KELA's 2022 cybercrime report found LockBit accounted for just under 30% of ransomware incidents in 2022. Just last week one of the group's affiliates was responsible for an attack on Britain's Royal Mail which is causing an ongoing "severe service disruption".

Jon DiMaggio, Chief Security Strategist at Analyst1, infiltrated the LockBit ransomware gang using fake personas and has just published a sterling report on what he calls the "human side of the operation". Although there have previously been leaks from ransomware groups that have shed light on how they work, this report provides a different perspective.

This report sheds light on why LockBit is now the largest group and how it found success. One early initiative the group took to garner notoriety and brand awareness amongst the criminal underworld was to sponsor a "Summer Paper Contest" on a Russian hacking forum. The top five papers received monetary rewards ranging from $1,000 to $5,000 (currency not specified) and was a unique approach for a ransomware gang.

The group has also invested in its ransomware. In addition to updated and faster encryption the group also made its ransomware platform easier to use with a point-and-click graphical user interface that made it much easier for affiliates to conduct ransomware attacks with less technical expertise required.

LockBit also undertook business model innovations that were very attractive to affiliates. In most Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) operations, the core group receives payments and passes a percentage cut to the affiliate, who sometimes doesn't get paid. LockBit turned this model on its head — the affiliate collects the ransom and passes a cut to the group.

This is interesting stuff, but the opportunities for disruption that spring to mind when reading the report are mouth watering.

DiMaggio points out that reputation is important as RaaS groups are competing for talented affiliates — without them there are no ransom payouts. This reputation is affected by what occurs on criminal forums and DiMaggio describes how LockBit's early reputation was damaged when it was the subject of an organised arbitration process on a criminal forum. An affiliate had complained that a bug in LockBit's ransomware meant it wasn't actually encrypting files, but just appending a ".lockbit" extension to them. The affiliate realised after they worked as a LockBit affiliate for several months that none of his victims had ever paid a ransom. The group had to work to recover from this reputational hit.

Competing ransomware groups also engage in public smear campaigns against each other, and LockBit is a serial offender here. One example DiMaggio cites is LockBit using news that a ransomware attack may have resulted in the death of a baby girl to insinuate that competing ransomware groups Hive or REvil were behind the attack. LockBit offered no evidence to support its claim, but the intention was clear – smear the competition as baby killers and steal their affiliates. (Some ransomware affiliates have moral standards, apparently.)

In both these examples it's pretty easy to see how, with the right access, these forums could be manipulated to spread distrust in the criminal community.

DiMaggio also infiltrated LockBit fairly easily. He told The Record that the group left him on its TOX encrypted messenger channel after he'd failed a job interview for a coding position. DiMaggio doesn't even speak Russian. He convinced LockBit members to speak English to him by starting off speaking in German. This is very funny.

Ransomware is here to stay, but this report reinforces our view that concerted government action, including the use of offensive cyber operations, will make a difference and reduce its impact.

DiMaggio concludes:

In my opinion, we need to conduct information warfare operations intended to inject propaganda and misinformation across dark web forums used by ransomware criminals. If criminals lose trust in the RaaS provider, they will not work for them. Paranoia, distrust, and concerns about losing revenue are common among ransomware affiliates. We need to play on this fear. This, in conjunction with attacks against ransomware services and infrastructure, would deny the resources that ransomware gangs provide to their affiliates. Driving distrust and causing intermittent service outages would frustrate criminals and affect the RaaS provider negatively. Regardless of how we address the issue, one thing is for sure, what we are doing now is not working, and it’s time for a change.

We agree.

Trigger Warning! Cyber Operations in Ukraine!

The Ukrainian government has released a detailed report (summary here) that contains many short case studies addressing the relationship between what it calls cyber, conventional, and information attacks by Russia's forces in its invasion of Ukraine.

The top line summary is that destructive cyber operations were "designed to increase the chaos of a conventional invasion, reduce the country's governability, and damage critical infrastructure". It says:

Cyberattacks are entirely consistent with Russia's overall military strategy. Moreover, cyber-attacks are often coordinated with other attacks: conventional attacks on the battlefield and information-psychological and propaganda operations. This effect was demonstrated in the autumn and winter of 2022, when, after a series of cyberattacks on the energy sector, Russia launched several waves of missile attacks on energy infrastructure. While simultaneously launching a propaganda campaign to shift responsibility for the consequences (power outages) to Ukrainian state authorities, local governments, or large Ukrainian businesses.

It also describes the evolution of Russian offensive cyber priorities. At the beginning of the invasion, these were aimed at disrupting communications and therefore impairing the functioning of the military and government. Later in the conflict, they "focused on inflicting maximum damage on the civilian population".

In many of the cited examples, destructive cyber operations occurred at the same time and place as conventional attacks, which demonstrates at least some level of common tasking. For the most part, however, the attacks didn't enable or enhance the kinetic attacks, but appeared intended to cause extra disruption and chaos. It's the kitchen sink approach rather than a closely coordinated and integrated approach aimed at achieving some sort of synergy.

Our view is that disruptive cyber operations in wartime are best used as force multipliers rather than as a siloed capability that is employed at the same time and place to achieve a similar effect. Otherwise, why use cyber capabilities when you can just use more artillery or more missiles? What is it getting you that you can't achieve with more things that go bang?

We've discussed this before, particularly in the context of Microsoft's claims of significant coordination between Russia's cyber and conventional forces. We'll recap our beef with Microsoft's claims briefly here because an occupational hazard is that people sometimes attempt to rebut our arguments without understanding them in the first place.

In short, we believe Microsoft has not provided enough evidence to back up some of its claims about extensive coordination between Russian cyber and conventional operations. Microsoft's report makes very strong claims about the level of coordination and integration:

On several occasions the Russian military has coupled its cyberattacks with conventional weapons aimed at the same targets. Like the combination of naval and ground forces long used in an amphibious invasion, the war in Ukraine has witnessed Russian use of cyberattacks to disable computer networks at a target before seeking to overrun it with ground troops or aerial or missile attacks.

This doesn't merely describe shared targeting priorities, but instead describes a high level of integration and coordination between cyber and conventional forces. But the evidence Microsoft provides to back up this claim is not strong and we were not alone in this criticism. Our first piece examining this issue provides Western examples of closely coordinated operations that we think meet the bar Microsoft itself set.

Even this Ukrainian government report doesn't reinforce Microsoft's claims. It hints that the tight coordination Microsoft asserted could be happening, but doesn't provide convincing evidence. It cites an attack on the DTEK Group, Ukraine's most significant private energy company, from July last year where missile and cyber attacks occurred at the same time and says that "the simultaneity of cyber attacks and missile strikes against energy infrastructure is designed to scale the negative consequences and increase the damage from the attack".

It's not clear from the report if the cyber and conventional attacks here caused complementary effects that reinforced or enhanced each other, or if they were simply additive and caused more damage because they, well, caused more damage.

There are a couple of clear examples from the Russia-Ukraine conflict that do demonstrate complementary effects, but they all occurred at the start of the war. Russia's cyber attack on Viasat is one of them. It achieved an effect — synchronised to events on the ground — that could not be executed with conventional forces.

The bulk of the observed Russian cyber activity — cited by the likes of Microsoft and in this report from the Ukrainians — doesn't fit into the Viasat category. Cyber and conventional forces sharing priorities is not the same as truly coordinated action. It's the difference between combined arms warfare and warfare with more arms.

We keep splitting this hair because we think an accurate account of the war in Ukraine is important and that policymakers still have questions about the role of destructive cyber operations in wartime. What exactly are these operations good for? What should militaries hope to achieve and how much should they invest in these capabilities?

We won't get to the right answers if these operations aren't described accurately.

Three Reasons to be Cheerful this Week:

Europol disrupts €2m scam: Europol announced that authorities from Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany and Serbia cooperated to crack down on multiple call centres that engaged in fraudulent "pig butchering" cryptocurrency investment scams. 15 people were arrested, over 260 questioned and about USD$1m in cryptocurrency and €50,000 in cash seized.

BianLian ransomware decryptor: Avast has released a free decryptor for BianLian ransomware after identifying a flaw in the encryption.

Meta sues surveillance service: Meta has launched legal action against a service that creates fake accounts on its services to scrape user data. These types of services are part of the surveillance-for-hire industry yet we don't think they have the high profile that will result in truly significant government action. So commercial lawsuits are good news.

Sponsor Section

Seriously Risky Business is supported by the Hewlett Foundation's Cyber Initiative and corporate sponsor Proofpoint.

Okta and Passwordless Authentication

Risky Business publishes sponsored product demos to YouTube. They're a great way for you to save the time and hassle of trying to actually get useful information out of security vendors. You can subscribe to our product demo page on YouTube here.

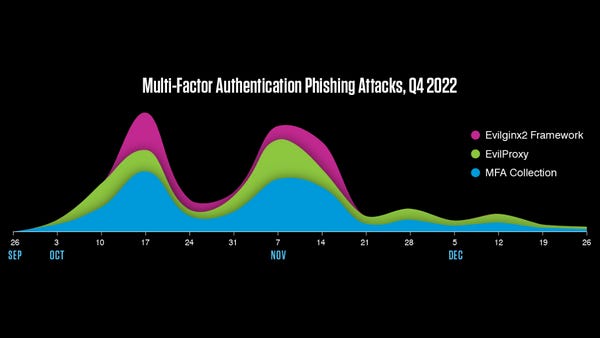

In our latest demo, Brett Winterford and Harish Chakravarthy demonstrate to host Patrick Grey how Okta can be used for passwordless authentication. These phishing resistant authentication flows — even if they are not rolled out to all users — can also be used as a high-quality signal of phishing attempts that can be used to trigger automated follow-on actions.

Shorts

Fear of War Drives Russian Phishing

Russian cyber security firms have found that hackers have used the fear of "moblisation", i.e. conscription into Russia's war effort, to steal Telegram credentials in a successful large-scale campaign. The lure used was a link to a site that purportedly contained the list of people who could be drafted into the Russian army to fight in Ukraine this February.

It's not known who is behind the campaign, but it certainly makes sense for Ukrainian interests. In a Between Two Nerds podcast The Grugq thought that the best way for Ukraine to leverage the IT Army would be to get it to harvest credentials as an enabler for government cyber operations.

Frog: Don't Get Boiled

French General Aymeric Bonnemaison, the head of France's Cyber Defense Command, told French newspaper Le Monde (English coverage) that US Cyber Command hunt forward operations are helping countries defend themselves, but also potentially exposes them to US intelligence gathering.

We don't think the US IC would actually use this type of program to pursue access into allies' environments. Discovery of a program like this by an ally would be politically catastrophic.

Cyber Command conducts these defensive threat hunting operations at the invitation of partner nations, and has conducted them in at least 35 countries. The countries specified so far are all European countries and include Ukraine, Estonia, and Lithuania.

We do agree, however, that fears of spying will be on the minds of some policymakers in those countries and providing reassurances and guarantees is something the Americans should do.

Iran's New Mobile Surveillance System

The Citizen Lab has published a report on the Iranian government's efforts to build domestic mobile phone interception capabilities.

Chainalysis: Results of Cryptocurrency Sanctions Are Mixed

A new Chainalysis report examines the effects of US sanctions on different cryptocurrency exchanges. The exchanges Chainalysis examined were quite different as were the results. Not surprisingly Hydra Marketplace currency flows dropped to zero as the market was also seized by law enforcement. Tornado Cash, a decentralised mixing service, was quite badly affected by US sanctions. But Garantex, a high-risk exchange based in Russia actually saw trading volumes increase.

Risky Biz Talks

In addition to a podcast version of this newsletter (last edition here), the Risky Biz News feed (RSS, iTunesor Spotify) also publishes interviews.

In our last "Between Two Nerds" discussion Tom Uren and The Grugq find that most countries' use of cyber capabilities makes sense. Except for the US. They are in a different position and the development of cyberspace as a domain of strategic competition is a net loss for them..

From Risky Biz News:

SweepWizard leak: SweepWizard, an app used by US law enforcement to coordinate multi-agency raids, exposed the exact location of upcoming raids along with sensitive details about both suspects and police officers alike. According to tech news outlet Wired, data on 200 raids, 5,700 suspects, and hundreds of police officers, mainly from California, leaked via the app. Since the leak, ODIN, the company behind SweepWizard, has taken down the app's website and iOS and Android store listings.

Spyware in Bangladesh: The Bangladesh government has bought spyware and surveillance tools from four Israeli companies using intermediaries in Cyprus, Singapore, and Switzerland. According to Israeli newspaper Haaretz, the buyers included the country's Interior Ministry, internal security agency, and armed forces. The tools, which included systems to monitor and intercept mobile and internet traffic and were worth almost $13 million, were bought through intermediaries because Bangladesh is one of 28 countries that don't recognize Israel as a state. [Haaretz/non-paywalled link]

Google Search and Ads have a major malware problem: Risky Business News examines the cybercrime trend toward delivery of malware to users via search results instead of via email-based delivery. This is called "SEO poisoning" or "SERP poisoning" where SEO stands for search engine optimisation and SERP for search engine results page.

Since late 2021, a trend has been emerging in the cybercrime ecosystem, with many operations dipping their toes back into SEO/SERP poisoning as a distribution tactic, either a replacement or a companion for classic email channels. (much more here)